Stepping into the theatre to watch David Mamet’s Sexual Perversity in Chicago was like walking into a party waiting to happen—the lights were dimmed, there was a bar up-stage with a beer pong setup on the wall, and to top it off, “Get Lucky” was playing in the background. This lustful, hungry ambience continued throughout the performance up until the end, when its inconclusiveness left me with blue balls. Nelson Patino, Jr., a recent alum of the City College, directed Mamet’s play, and judging by its outcome, he and his creative team were successful at sticking to common themes and ideas such as friendship, predator/prey relationships, sex, and love, which when all tied together made for a cohesive show.

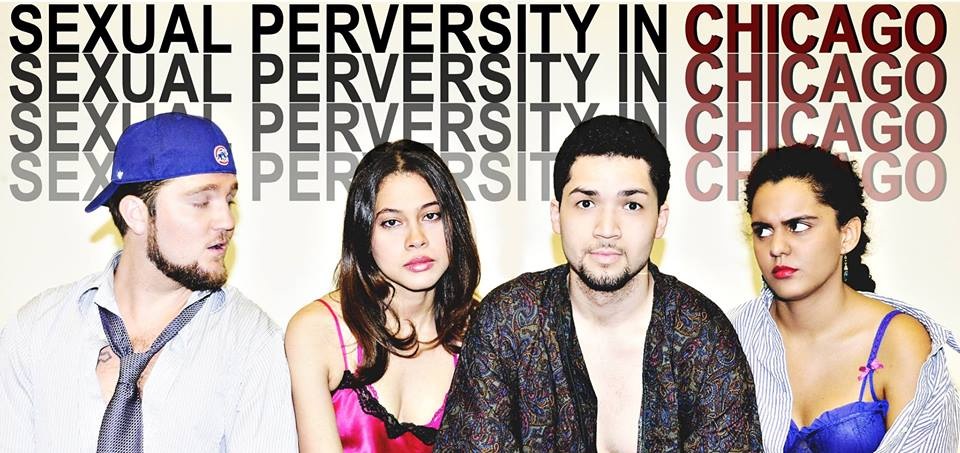

Costume designer Bianca Catalan kept the wardrobe stylish and appropriate to the different locations in the play (button-ups and ties at work, tank tops and shorts at home, for example). Set designer Kimberly Gomez and lighting designer Nikita Maturine worked together to make each location on stage, which were about six, distinct from each other so as to avoid confusion, and sound designer Daniel Scymanowicz kept the mood fun, casual, and realistic when the play called for it (Example: Wave and seagull sound effects at the beach). Patino and his designers created a well-rounded world for the actors (Diana Burgos, Ervin Vazquez, Matthew Thomas Burda, and Isabella Peralta) to play and explore their sexualities.

In Sexual Perversity in Chicago, as well as in the real world, men are more likely to be considered predators that prey on women. What Mamet did was point out how interchangeable the roles can be, and how women may also prey on men. At the top of the show, Burda’s character, Bernie, is at the bar speaking very crudely about sexual experiences he supposedly had with a girl that was “19 or 20” years old, while Vazquez’s character, Danny, listened on like a naïve schoolboy fascinated by the class clown—a directorial choice that highlighted who was in control. This opening scene put the males in a powerful position because their topic of conversation reduced women to sex toys. The shift in power began when Danny met Burgos’ character, Deb, and they eventually fell into a domestic relationship that quickly went awry. Eventually, Deb moves back in with Peralta’s character, Joan, and the two groups of friends continue on with their separate lives. The predator/prey relationship applies to both friendships as well; Bernie and Joan are the predators because they want to control what their friends do, even though they don’t admit it. Patino succeeds at portraying the struggle for power, even in nonsexual relationships.

It was an inspiration to watch the work of a classmate that walked the same halls and took the same classes that I still do. The production was a success because of Patino’s attention to detail and the apparently strong communication he maintained with his team regarding his vision. Every blocking choice, arrangement of set pieces, or beat changes felt significant and relevant to the theme being depicted. The result of these stylistic choices was more of an ability for an audience to empathize with the story’s characters.

One of the things that impressed me the most about this production was the treatment of the transitions. Mamet included many locations in his play, and while another director may have arranged for multiple set changes, Patino decided to put all the places on different sides of the stage. For example, the bar was up-stage center, Danny’s and Bernie’s workplace was center-right, and Danny’s apartment was center left. In order to make it clear to the audience that we were shifting from one place to another, the lights quickly blacked out on the entire stage except for where the director wanted us to look, which gave the play a cinematic feel.

The two main criticisms that I had with this production of Sexual Perversity in Chicago are the nudity and the ending. In regards to my first qualm, there was a scene where Danny and Deb had woken up from having sex and Danny got out from under the covers and he was completely naked. Although this play is inherently sex-based, the full-frontal was unnecessary because the same scene could have been performed without it, and it would have been twice as effective; the audience wouldn’t have been busy gawking at Ervin’s genitals with the amazement of pubescent tweens. My second frustration with the play was the abruptness of the ending, which is something the director had no control over, unless he cut it and ended it at another point. When the show was over, there were many audience members asking, “What?” and, “That’s it?” It was unsatisfying because we are used to watching plays and even listening to stories and music in which everything comes around full circle in the end. Mamet’s play ended after Danny and Deb’s breakup, and left the audience with a sense of “oh well, that’s life,” that we were not expecting.

Regardless, I would still recommend everyone to watch the CCNY Theatre Department’s production of Sexual Perversity in Chicago if it were still running. Why? Because it raises questions about sexuality and power that our generation is still trying to answer.

Verdict: 7.5/10